Mora – Land, Wool, and Democracy

November 17 – 19, 2011

I pulled into Holman, New Mexico, seven miles north of Mora, by mid afternoon to find my hosts Daniel and Rebecca in their vintage late-1800s adobe house with its brilliant scarlet corrugated tin roof and seven acres of fields down along the stream. Lengthening blue shadows of the mountains covered the north-south running valley in shadow and cold earlier than expected.

I pulled into Holman, New Mexico, seven miles north of Mora, by mid afternoon to find my hosts Daniel and Rebecca in their vintage late-1800s adobe house with its brilliant scarlet corrugated tin roof and seven acres of fields down along the stream. Lengthening blue shadows of the mountains covered the north-south running valley in shadow and cold earlier than expected.

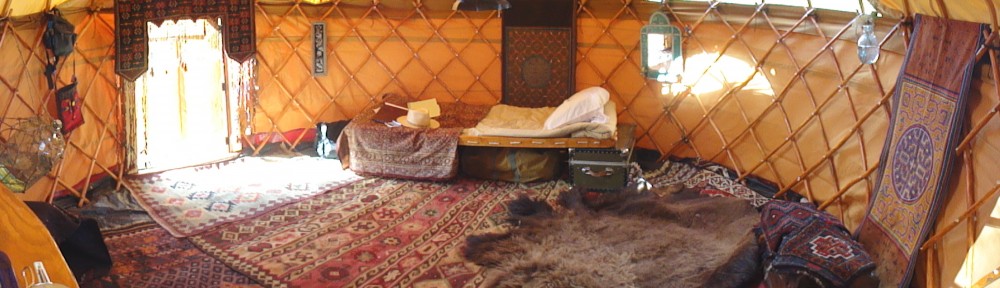

My hosts guided me along a grassy lane between their field and the neighbor’s to the low part where we’d pitch the yurt. A couple of errant horses had invaded the field but occupied themselves feeding on stubble. The recently mowed hayfield left nothing between the yurt and the onslaught of winds to come. This trip would be the structure’s first test of strength.

We scurried to unpack and set up before dark. A recalcitrant chimney flue threatened to abort the stove’s inaugural burn. Tired, we retreated to their cozy house for a collaborative meal of ratatouille of eggplants I brought and chard from their garden, glasses of superb Gruet pinot noir from Albuquerque, and Rebecca’s wheat and rye bread made moist with goat milk from her landlady’s ranch that we’d visit the next day. These folks know good food, having worked as interns on an organic farm and now with their own garden large enough to supply the local market.

We relished our common dedication to wholesome local food, fiber arts, and low-impact living. I met the couple at the Quivira Coalition’s annual meeting, just weeks before. The meeting celebrated the New Agrarians and brought mentors together with charismatic young farmers and cowboys from around the country, from rural and urban places. With Quivira’s help Daniel had served as an apprentice to learn about fiber arts. He gave an eloquent summary of his experience at the conference, where he described his journey with early art making, through agriculture, and back to fiber arts because of fibers’ blending of animals, land, and aesthetics. We connected directly about making felt. He showed me wild examples of stones and bars of soap covered in felt, sandals that looked like they could have been worn by Christ, a stool made from a milk crate covered in about three-quarters of an inch of felt, and compelling necklaces of rolled felt he shapes over a drumstick or a skewer which, upon removal, allow for shrinkage. Daniel grew up in Mexico and Chicago, so his aesthetics combine a sense of self-reliance with utility that infuses common objects with playful materials and designs.

European immigrants settled Mora in 1835 (Pearce 1965) with settlers from Las Trampas, Picuris, and Embudo (Noble 1994). In 1855 St. Vrain arrived and built a stalwart, but today crumbling, stone flour mill just down the street from the wool mill. Mora was a renowned wheat producer and St. Vrain’s flour made its way to Fort Union and Fort Garland in Colorado. Brainyzip.com claims 1,390 residents in Mora split among 723 housing units spread out over 77.5 square miles. 87.5% of the population is Hispanic or Latino, in contrast to 12.5% nationally; most speak Spanish at home. A 23% vacancy rate of housing units testifies to greener economic pastures elsewhere. The population has almost three times the national poverty rate and half the per capita income. Then again, owner-occupied housing is more common than nationally, suggesting many live without a mortgage, having inherited land and housing along a chain of ancestors going back several generations.

That first night the wind crashed like big surf, shaking and popping the yurt sharply through three phases of the night beginning with starry blackness, a rising moon, and dawn’s first light. Alas, the jet stream was parked over Mora for the next two days. In the dark I could hear a vicious wind approach like a freight train shooting down from the stratosphere and dragging its wagon along the ridges of the valley. Just enough of its power reached the valley floor to shock me out of a fitful sleep to wonder how long the canvas would hold. Nonetheless upon daybreak the score was Tempest 0, Yurt 1.

Local Wool Industry

After a quick breakfast I joined Daniel and Rebecca for the 7 mile trip to Mora and Tapetes de Lana weaving center where they weave, spin wool, keep shop, and tutor young knitters. The center is run by Carla, their landlady, boss, and mentor. She and her partner Richard live up on the mountain outside of Cleveland, the small town between Holman and Mora.

I spent the morning learning about Tapetes de Lana. The center has an inviting front gallery with several floor looms, wood burning stove, yarn and fiber supplies, consignment art, and a coffee bar. Carla was fiber arts director for 18 years at El Ranchos de las Golondrinas historical demonstration site outside of Sante Fe. Around 2004 she obtained USDA Rural Development funds and other grants to build a wool mill in Mora. Since then her team has built new buildings and populated them with repurposed industrial milling equipment from failed textile mills around the US. Imagine a semi-tractor trailer pulling into town with a multi-ton behemoth of iron, gears, and spindles.  The carding machine is so huge they built the building around it. That giant is one of 15 originally destined for the scrap heap, but now it is the workhorse of the shop. She has machines for washing, drying, carding, spinning, steaming, and plying strands into yarn.

The carding machine is so huge they built the building around it. That giant is one of 15 originally destined for the scrap heap, but now it is the workhorse of the shop. She has machines for washing, drying, carding, spinning, steaming, and plying strands into yarn.

The mill can blend wool from various breeds of sheep with alpaca or angora, thereby creating yarns that make aficionados drool at the touch. There is a 40-spool spinning frame that is programmed the Victorian way with gears to produce yarn of desired thickness and twist. Carla expects to install a worsted mill enabling wool fibers to line up in parallel for exceptionally fine, strong yarns of the sort used to make elegant suits. The existing woolen mill produces softer yarns from Merino wool. Spun yarns are dyed and offered for sale in the gallery or woven into rugs of greater value. Having done some weaving myself, the rug prices seem low given the quality of material and heritage of the Rio Grande style they celebrate and take inspiration from.

A wool industry makes a lot of sense in this mountain economy, where folks with land grow some sheep for meat but find themselves with a pickup truck full of wool after the slaughter. They bring it to the mill in exchange for a percent returned as spun, dyed yarn to use, sell, or trade. Nonetheless, skilled labor is needed and scarce. Machine operators need to be comfortable with gear boxes, mathematical calculations, and savvy about what quality finished products look and feel like. And they need to be willing to live in a small rural community.

Carla can find surplus textile machinery because textile manufacturing has been outsourced to Asia, where giant mills with dozens of machines handle tons of fiber. So I asked Carla, “How do you expect to make this relatively small mill work in the face of Asian competition?” She is clear, “We fill a niche for our medium size customers.” There is a yarn retailer who contracts with Carla to spin custom blended yarns of wool, angora and alpaca. The popularity of the superior, custom product has resulted in larger orders each time.

Carla’s marketing strategy revolves around the gallery. Yarn, roving, and finished rugs in the traditional Rio Grande style are found in quantity. Today Rebecca sold one of her table runners made of lustrous, long-staple Lincolnshire wool while I toured behind the scenes with a large group of fiber enthusiasts who lingered afterwards to buy materials from the gallery. Some of the yarn is purchased at deep discounts and finds its way to retail outlets throughout New Mexico and the US.

Commerce is a challenge in any rural mountain village. Yet, Merle Witt, President of the Mora Valley Chamber of Commerce spoke with me about innovation and intention. “I contend…Mora has a kind of a bifurcated economy. There are the families that lived here for many, many years. They have land, maybe not very much income, the local families with histories going back generations. Then there are people like myself, honestly, who, in my case I’m a retired military officer, spent 26 years in the air force, I have a military pension. I know of [many people who] come to Mora, they just want to live in the rural environment, but we have an income. So if there’s going to be economic opportunity like the [Mora Valley] Ranch Supply Store, then the first place to look would be to the people who moved here in the last 10, 15 years… because they probably have the resources. A lot of these people invest as sort of a contribution to the community. Not that they want to give their money away, but they recognize that it’s going to be several years before there’s any payback, even then it’s going to be not very much. But they live in this community and that’s their way of making it better.”

What goes around comes around. I asked Mr. Witt if there were any other niches that are open for people to come in and set up a new store. He answered, “We need a department store. Where you can buy basic household good items, clothes, work clothes, kitchen items. We don’t need people selling food. We have that. But the basic day to day items, why can’t we have that here?” Curiously, they did, back in the day. As Carla’s partner Richard and I drove by a quaint old abandoned mercantile on the corner of Encinal Road in Cleveland, just up the road from Mora, Richard explained “They had everything” until internal family squabbles tanked the enterprise.

After lunch of classic bean burritos at the homey Little Alaska café, I wondered off to see the many old adobe buildings around town, eventually coming to the abandoned St.Vrain grain mill, with its rusted water wheel. In his delicious fictionalized history People of the Valley, Frank Waters makes the mill the site of the never-conjugated marriage between Maria de Valle and aged Don Fulgencio whose deception of Maria’s heart was solely to acquire her land through marriage as part of a scheme to build a reservoir in the valley. Today the lovingly restored Cleveland Roller Mill is open seasonally for tours and its own festival of quality arts.

Ranch Life

Later in the afternoon, Richard hosted me on his ranch for a horseback tour. At the gate he jumped out of Daniel’s Jeep and caught his four-year old mare, placing a makeshift halter of bailing twine over her neck and through her mouth like a bit, “Hippie style.” He grabbed her withers and pulled himself up like a practiced gymnast. They loped up the hill to one of his tack sheds to saddle her up. The image of the two charging away up the muddy track gave a sense that a willing horse is appropriate technology. Grass-fed, carbon neutral, self-regenerating, trainable, powerful. He rode off to a pasture to gather her brother for me to ride. At the second tack shed full of dusty trail-worn saddles, a bucket of farrier tools, rain gear, and chaps, Richard pulled out a bridle and bit from his deceased mule which succumbed after being accidentally trapped under a fence. Seeing that this was no dude ranch, I confessed somewhat sheepishly that although I was raised riding Western style I currently ride English and am unfamiliar with Western tack. Richard shrugged off the English style by saying, “It is still a saddle.” He and his father used to guide folks on wilderness pack trips in the Pecos, so he was wise about choosing an appropriate horse for me and helping adjust the stirrups.

He has lived on the ranch his entire life, having inherited the land from his father and built his own house at 16. He and Carla manage several working horses, a small cattle herd, 40 sheep, over a dozen goats, a handful of capable sheepdogs, and a big family garden with turnips, greens, and other crops. There is a giant two-story, unfinished and weathered palace of chipboard across the lane from his horse corral. That project started with an early marriage but lasted about as long. Now his son, a bright lad with designs on law school, shares Richard’s original house with Carla. With 350 acres, much in conifer forest at 9000 feet, Richard is using state funds to thin the forest to reduce fire risks while opening space for new meadows that will feed his herds. Fire will spread across ranch boundaries, going or coming, so the thinning project benefits both Richard and his neighbors. As part of the original Mora Valley land grant he has ample water rights that enable him to divert water here and there as a management tool. We saw a patch of troublesome oaks that he doomed to die from wet feet, thereby relinquishing space for forage grasses to return. It was November, with blustery winter conditions and ice forming in the ditches, so I asked, “Why are you irrigating now, when things aren’t growing?” His answer made a lot of sense; he was storing water in the soil for next season rather than having to catch up to high demand during the hot part of the year. Too cold to evaporate, he could build reserves in the ground where it would be needed next year. I relished the excitement of riding a horse that was willing to run yet kind enough to listen to my requests to hold back. He voluntarily bounded up steep slopes with the energy a six-cylinder car delivers when climbing a hill with cruise control on.

That evening, Carla prepared a casual feast of ranch-raised beef, turnips from the root cellar, carrots that Daniel dug from the garden that afternoon, and quinoa. We washed it down with beer and local mead which was reminiscent of sauvignon blanc. Dinner conversation took us to Richard and Carla’s work with Daniel Pennock Democracy Schools, which in the tradition of naming great institutions such as Stanford University for deceased youth, the Democracy Schools are named for a boy in Pennsylvania who died after exposure to sewage sludge (http://celdf.org/democracy-school). The Mora community study group has been learning about citizen-based democracy because of threats to water and air quality posed by oil and gas development.

Richard and Carla have their livestock processed at Mel’s Custom Meat in Romeo, Colorado to earn the USDA stamp for their brand, Los Vallecitos Meats. The desire for USDA certification means a 264 mile round trip requiring about six hours and close to $50 worth of fuel. Other options include the Taos County Economic Development Center’s Mobile Matanza (116 miles round trip) or the Ft. Sumner Processing facility (368 miles round trip). Before leaving, we purchased two pounds of lamb chops for dinner the next day, a dinner subject to a change of plans.

Stress Test

I returned to the yurt around 10:00 that evening, under a clear canopy of the Milky Way and battering winds like those that had beat up the yurt all day long, leaving it a tad distorted in shape. The new winter cover over the central opening at the top had shifted, thanks in part to the hole created by the thimble for the stove pipe. Adjustments would require untying some of the ropes. In the wind it was impossible to untie more than one corner at a time without turning the canvas into a kite, so I opted to leave things a bit askew and hope for the best. Alas, great slugs of wind kept working their way under or across the opening, creating a Venturi effect that opened gaps down along the base of the canopy, especially around the door frame. Tense pulling on the cover dragged at its tie-ropes, further shifting the outer tension band which is key to the yurt’s structural integrity. Circumstances were setting the stage for catastrophic failure.

All night long explosive bursts of wind shook and snapped the canvas while straining the frame. Suddenly at 5:30 a.m. a blast cracked one of the wooden members, announcing a more urgent situation had arrived. I set to work packing my belongings for a hasty take-down. By 6:00 a.m. I was outside, holding down the flapping canvas with one hand and dialing to call Daniel and Rebecca in the hope that they slept with their cell phone on. I had to consciously lie to myself that I had things under control; otherwise panic would have taken over. Thankfully, Rebecca called me right back and soon both my hosts arrived to take down the structure. Again, the yurt revealed assumptions coded into the architecture itself, that as a family home many hands are available to deal with extreme weather and the more routine jobs of pitching and striking camp.

Now a homeless nomad I was ready to leave after two fitful nights. Daniel and Rebecca kindly shared half the lamb to take with me, along with a shiny jar of home-made toasted kale crisps seasoned with salt and lemon – a terrestrial seaweed if you will – exotic and nutritious. A mile down the road I received a call from Rebecca who discovered that I’d left two cherished yurt books behind, so I returned to pick them up. Sleepily back on the road again I realized that the stash of firewood they had provided for the yurt was still in the back of the van. Another call and we decided that the wood would be repurposed later, its first gig in my fireplace on Thanksgiving, which left a cherished albeit smoky legacy inside my house as a reminder of the earthy visit to Mora. Another parcel of the wood will find use baking bread in a traditional horno at the university for our end-of-semester pot luck.

Since returning, Lee, a Native man who heard of the yurt experience, has recommended a blessing ceremony, to protect the yurt and hopefully to heal the trauma.

Modifications

The DIY yurt community will appreciate several design modifications planned for the future.

1) Include a traditional woven band, two or so inches wide, to run around the circumference of the roof, taking loops around each roof strut near its bend. The band will bridge between adjacent struts so that the tie-down ropes from the hoop cover do not load the canvas and create gutters that catch wind.

2) Insert pins through the mortise and tenon joints of the door frame. The unpinned joints actually opened during the wind storm; most undesirable.

3) Add 3-4 foot-long triangles to corners of the hoop cover to keep wind from getting underneath.

4) A 12-inch, drop-down extension is needed for the bottom edge of the canopy to reduce the chance of wind getting under it and opening gaps at the top of the wall.

5) Modify the exterior hold-down harness to put diagonal bands across the outside of the canopy in the tradition of Turkmen yurts (http://www.solaripedia.com/images/large/3693.jpg) especially over the door.

Leeway exists during setup to make the diameter wider, thereby lowering the roof profile by about a foot. That would reduce the leverage the wind applies to the walls via the roof struts.

Sources

Noble, David Grant (1994) “Mora” Pueblos, Villages, Forts & Trails: A Guide to New Mexico’s Past University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, pp. 175-179.

Pearce, T. M. (1965) “Mora” New Mexico place names; a geographical dictionary University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, NM, p. 104.